Immunohistochemistry Patterns in Lymphoma Diagnosis: A Tertiary Care Experience

Dr. Md. Adnan Hasan Masud1, Dr. Kazi Mohammad Kamrul Islam*2, Dr. Shahela Nazneen3, Dr. Gazi Yeasinul Islam4, Dr. Nasrin Akhter5

1Associate Professor, Department of Haematology, Bangladesh Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Assistant Professor, Department of Haematology, Bangladesh Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Associate Professor, National Institute of Kidney Diseases and Urology, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Medical Officer, Department of Haematology & BMT, Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

5Assistant Professor, Department of Haematology, Bangladesh Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Dr. Kazi Mohammad Kamrul Islam, Assistant Professor, Department of Haematology, Bangladesh Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Received: 23 June 2025; Accepted: 30 June 2025; Published: 15 July 2025

Article Information

Citation: Dr. Md. Adnan Hasan Masud, Dr. Kazi Mohammad Kamrul Islam, Dr. Shahela Nazneen, Dr. Gazi Yeasinul Islam, Dr. Nasrin Akhter. Immunohistochemistry Patterns in Lymphoma Diagnosis: A Tertiary Care Experience. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 700-704.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Despite the well-established role of immunohistochemistry in lymphoma diagnosis, there remains a paucity of region-specific data on its application, particularly in resource-limited settings. The purpose of the study is to assess immunohistochemistry patterns in lymphoma diagnosis within a tertiary care setting.

Aim of the study: The aim of the study was to evaluate immunohistochemistry patterns in lymphoma diagnosis within a tertiary care setting.

Methods: This observational study at the Department of Haematology, BSMMU, Dhaka (January 2024–December 2024) included 30 patients with confirmed lymphoma who underwent immunohistochemical analysis and had complete data. Positivity thresholds were >30% for CD20/CD3, >50% for BCL2/BCL6, with Ki-67 assessed in hotspots. Lymphomas were classified per WHO 2022, and data analyzed using SPSS v26.

Results: Among 30 lymphoma cases, the mean age was 45.0 years, with 70% male predominance and 73.3% presenting with painless lymphadenopathy. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (80%) was more common than Hodgkin lymphoma (20%). B-cell NHLs comprised 75%, with DLBCL being the most frequent subtype (37.5%), while T-cell NHLs accounted for 25%. CD20 was positive in 66.7% overall and 83.3% of B-cell NHLs; BCL2 in 50%, especially in DLBCL and FL. CD3 marked 66.7% of T-cell NHLs. HL cases showed CD15 (83.3%) and CD30 (100%) positivity. The mean Ki-67 index was 45%, exceeding 60% in aggressive subtypes.

Conclusion: Immunohistochemical profiling proves essential for accurate lymphoma classification and informed clinical decision-making.

Keywords

Immunohistochemistry, Lymphoma, Diagnosis

Immunohistochemistry articles, Lymphoma articles, Diagnosis articles.

Article Details

Introduction

Lymphoid neoplasms encompass a broad spectrum of disorders, primarily categorized into two major clinicopathologic groups: Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL). These malignancies arise from clonal proliferation of hematolymphoid cells that morphologically and immunophenotypically resemble their normal counterparts [1]. Lymphomas pose a growing public health concern globally due to their diverse clinical presentations and variable prognoses. In India, the age-adjusted incidence of NHL is estimated at 2.9 per 100,000 males and 1.5 per 100,000 females [3,4], emphasizing the rising burden and the critical need for accurate diagnostic tools. Accurate diagnosis and classification of lymphomas require a multimodal approach incorporating morphologic evaluation, immunophenotyping, and molecular genetics [5–8]. Although histologic assessment laid the foundation for early lymphoma diagnosis, the advent of immunohistochemistry (IHC) has significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy [9]. Today, the combination of histopathology and IHC forms the cornerstone of lymphoma diagnostics [10]. Immunophenotyping is especially valuable in confirming lineage and delineating subtypes, particularly when histology and clinical data are inconclusive [11,12]. This precise classification is essential, as it directly informs treatment planning and prognostication. IHC enables accurate identification of lymphoma subtypes through the use of lineage-specific markers such as CD45, CD3, CD20, CD5, CD23, cyclin D1, BCL2, CD15, CD30, and Ki-67 [13]. These markers help distinguish between B-cell and T-cell lymphomas and facilitate subclassification according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system [14,15]. The WHO classification of hematopoietic and lymphoid tumors has undergone several updates (2001, 2008, 2016), with the latest fifth edition (WHO-HAEM5) adopting a more flexible diagnostic framework that permits class-level diagnosis even in the absence of complete criteria. This evolution underscores the indispensable role of IHC in hematopathology, particularly in settings with limited access to molecular diagnostics. Despite the well-established role of IHC in lymphoma diagnosis, there is a notable lack of region-specific data on its implementation, especially in resource-constrained environments. Much of the current literature originates from high-resource settings, leaving a gap in understanding how IHC patterns manifest across diverse populations and institutional contexts. Furthermore, variability in marker expression and interpretation highlights the need for localized studies assessing IHC’s diagnostic utility in everyday clinical practice. The purpose of the study is to assess immunohistochemistry patterns in lymphoma diagnosis within a tertiary care setting.

Objective

- • To evaluate immunohistochemistry patterns in lymphoma diagnosis within a tertiary care setting.

Methodology & Materials

This observational, descriptive study was conducted at the Department of Haematology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh, between January 2024 and December 2024. A total of 30 patients were included in the study, who were selected based on specific inclusion criteria for the evaluation of immunohistochemical (IHC) marker expression patterns in the diagnosis and classification of lymphoma.

Inclusion Criteria:

- • Patients of all ages with histologically confirmed diagnosis of lymphoma.

- • Patients who underwent immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis as part of their diagnostic work-up.

- • Cases with complete clinical, histopathological, and IHC data available.

Exclusion Criteria:

- • Patients with inconclusive histopathological or IHC findings.

- • Patients previously treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

- • Inadequate biopsy samples unsuitable for IHC analysis.

Demographic, clinical, and pathological data (lymphoma type/subtype, IHC expression) were extracted from electronic medical records and pathology archives. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4µm) underwent automated IHC staining (Ventana BenchMark XT) using antibodies against CD20 (L26), CD3 (PS1), CD15 (MMA), CD30 (Ber-H2), BCL2 (124), BCL6 (PG-B6p), Ki-67 (MIB-1), Cyclin D1 (SP4), and TdT (Sen28), with appropriate controls. Positivity thresholds were: >30% tumor cells for CD20/CD3 (membranous), >50% for BCL2/BCL6 (nuclear/cytoplasmic), and Ki-67 in hotspots. Lymphomas were classified per WHO 2022 criteria. Statistical analysis (SPSS v26) included descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, mean±SD).

Results

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population (n = 30)

|

Variable |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Age Group (years) |

0–20 |

2 |

6.7 |

|

21–40 |

10 |

33.3 |

|

|

41–60 |

12 |

40 |

|

|

>60 |

6 |

20 |

|

|

Mean Age ± SD |

45.0 ± 17.0 |

||

|

Sex |

Male |

21 |

70 |

|

Female |

9 |

30 |

|

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 30 patients included in the study. The mean age was 45.0 ± 17.0 years. Most patients were in the 41–60 years age group (12 patients, 40.0%), followed by 21–40 years (10 patients, 33.3%), >60 years (6 patients, 20.0%), and 0–20 years (2 patients, 6.7%). Regarding sex distribution, 21 patients (70.0%) were male and 9 patients (30.0%) were female. The most common clinical presentation was painless lymphadenopathy, observed in 22 patients (73.3%), while 8 patients (26.7%) presented with B symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and night sweats.

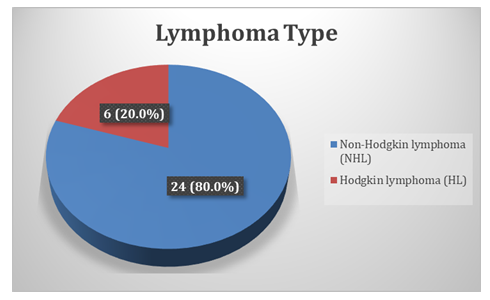

Figure 1 presents the classification of lymphoma cases based on histopathological diagnosis. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) was the predominant type, observed in 24 cases (80.0%), whereas Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) was identified in 6 cases (20.0%).

Table 3. Distribution of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) Subtypes (N = 24)

|

NHL Subtype |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

B-cell lymphomas |

18 |

75 |

|

• DLBCL |

9 |

37.5 |

|

• Follicular lymphoma |

3 |

12.5 |

|

• CD30+ B-cell lymphoma |

2 |

8.3 |

|

• Small lymphocytic B-cell lymphoma |

1 |

4.2 |

|

• Burkitt lymphoma |

1 |

4.2 |

|

• Other B-cell* |

2 |

8.3 |

|

T-cell lymphomas |

6 |

25 |

|

• Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma |

2 |

8.3 |

|

• Precursor T-cell lymphoma |

1 |

4.2 |

|

• Other T-cell** |

3 |

12.5 |

|

Total |

24 |

100 |

Table 3 presents the distribution of NHL subtypes among the 24 patients diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma in this study. B-cell lymphomas were predominant, comprising 75.0% of all NHL cases. The most common B-cell subtype was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), accounting for 37.5%, followed by follicular lymphoma (12.5%), CD30+ B-cell lymphoma (8.3%), small lymphocytic B-cell lymphoma (4.2%), Burkitt lymphoma (4.2%), and other B-cell variants (8.3%). T-cell lymphomas represented 25.0% of the cases, including precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (8.3%), precursor T-cell lymphoma (4.2%), and other T-cell types (12.5%).

Table 4. Immunohistochemical Marker Expression and Diagnostic Correlation in Lymphoma Cases (N=30)

|

Marker |

Positive Cases (n) |

Overall % |

Key Diagnostic Associations |

|

CD20 |

20 |

66.70% |

B-cell NHL (20/24; 83.3%) |

|

BCL2 |

15 |

50.00% |

B-cell NHL (15/24; 62.5%).DLBCL/FL (100%) |

|

CD3 |

4 |

13.30% |

T-cell NHL (4/6; 66.7%) |

|

CD15 |

5 |

16.70% |

Classical HL (5/6; 83.3%) |

|

CD30 |

6 |

20.00% |

Classical HL (6/6; 100%).CD30+ B-NHL (2/24; 8.3%) |

|

Ki-67 Index |

Mean 45.0% |

>60%: Aggressive subtypes (DLBCL, Burkitt, ALCL) |

|

Table 4 presents the immunohistochemical (IHC) marker profiles observed among the lymphoma cases in this study. CD20 was the most frequently expressed marker, detected in 66.7% of cases overall and in 83.3% of B-cell NHL cases (20/24). BCL2 was positive in 50.0% of cases and strongly associated with B-cell NHL (62.5%), particularly in DLBCL and follicular lymphoma where expression was universal. CD3 expression was noted in 13.3% of cases, corresponding to 66.7% of T-cell NHL cases. Among Hodgkin lymphoma cases, CD15 and CD30 were expressed in 83.3% and 100%, respectively, confirming their classical HL immunophenotype. Additionally, CD30 was positive in 8.3% of B-cell NHL cases, specifically in CD30+ subtypes. The Ki-67 proliferation index had a mean of 45.0%, with values exceeding 60% in aggressive subtypes such as DLBCL, Burkitt lymphoma, and ALCL, highlighting its prognostic utility.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate immunohistochemical (IHC) patterns in lymphoma diagnosis within a tertiary care setting. Using a structured approach involving WHO 2022 classification criteria and standardized IHC protocols, we assessed 30 histologically confirmed lymphoma cases at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Dhaka. The analysis highlighted the diagnostic utility of IHC in accurately subclassifying lymphoma types and elucidating marker expression profiles that support both diagnosis and prognostication. The demographic profile of our study population showed a mean age of 45.0 ± 17.0 years, with the majority of patients (40%) falling within the 41–60 years age group. Males predominated, constituting 70% of the cases. These findings are consistent with previous studies such as Dey et al.[16], who reported a similar mean age of 44.5 ± 17.9 years with a majority male population. Similarly, Alam et al.[17] documented a mean age of 46 years in their cohort, reflecting a comparable age distribution. The male-to-female ratio in our study (approximately 2.3:1) is also in line with the findings of Jahan et al.[18], who reported a male predominance with a ratio of 3:1. This consistent demographic trend across studies underscores the higher incidence of lymphoma among middle-aged males in similar tertiary care settings. Notably, the most common clinical presentation in our study was painless lymphadenopathy, seen in 73.3% of patients. This is in agreement with broader analyses of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, where more than two-thirds (>66%) of patients typically present with painless peripheral lymphadenopathy at diagnosis [19]. These demographic and clinical patterns reaffirm the importance of early recognition of typical presentations in high-risk groups to facilitate timely diagnosis and management of lymphoma. In the present study, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) accounted for the majority of cases (80.0%), while Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) comprised 20.0%. Aslam et al. [20] reported NHL in 74.6% of lymphoma cases and HL in 25.3%, supporting the trend observed in our cohort. This consistent predominance of NHL across various studies underscores its higher burden in the regional population and emphasizes the need for focused diagnostic and therapeutic strategies tailored to its subtypes.

In our study, B-cell lymphomas represented the predominant group among Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (75.0%), with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) emerging as the most common subtype (37.5%). This distribution closely mirrors findings from Akhter et al.[21], who reported DLBCL in 34.0% of cases, and Lisa et al.[22], who observed an even higher incidence of DLBCL at 58.2%, affirming its global predominance in NHL. Additional B-cell variants detected in our study population comprised follicular lymphoma (12.5%), CD30+ B-cell lymphoma (8.3%), small lymphocytic lymphoma (4.2%), Burkitt lymphoma (4.2%), and a minor fraction of other B-cell subtypes (8.3%), reflecting the diverse spectrum of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. T-cell lymphomas constituted 25.0% of the cases, with precursor T-lymphoblastic and other T-cell types contributing to this subset, consistent with the lower but clinically significant prevalence of T-cell NHL observed in most studies. These findings support the crucial role of immunohistochemistry in delineating lymphoma subtypes for accurate diagnosis and management in tertiary care settings.

In our study, immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed CD20 positivity in 66.7% of all lymphoma cases and in 83.3% of B-cell NHLs, reinforcing its role as a reliable B-cell marker. This is comparable to findings by Adomako et al.[23], who reported CD20 expression in 89.4% of NHL cases, predominantly of B-cell origin, underscoring the marker’s essential role in both diagnosis and targeted therapy. BCL2 was expressed in 50.0% of our cohort and was consistently positive in all cases of DLBCL and follicular lymphoma, a result consistent with the observations of Skinnider et al.[24], who found BCL2 positivity in 51% of DLBCL and 89% of FL cases, particularly those with t(14;18) translocation. CD3 was positive in 13.3% of all cases and in 66.7% of T-cell NHLs, confirming its specificity as a pan–T-cell marker. Among Hodgkin lymphoma cases, CD15 and CD30 were expressed in 83.3% and 100% of classical HL cases respectively, aligning with the established immunophenotypic profile of Reed-Sternberg cells. The Ki-67 proliferation index averaged 45.0% across the cohort, with levels exceeding 60% in aggressive subtypes like DLBCL, Burkitt lymphoma, and ALCL, consistent with its known association with high-grade lymphomas. These findings collectively highlight the critical utility of IHC markers in subclassifying lymphomas and guiding clinical decision-making.

Limitations of the study

This study had some limitations:

- • The study was conducted in a selected tertiary-level hospital.

- • The sample was not randomly selected.

- • The study's limited geographic scope may introduce sample bias, potentially affecting the broader applicability of the findings.

Conclusion

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma emerged as the predominant type among patients in this study, with B-cell subtypes accounting for the majority, particularly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemical markers such as CD20 and BCL2 were strongly expressed in B-cell lymphomas, while CD3 was more specific to T-cell variants. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma cases consistently expressed CD15 and CD30, aiding in definitive diagnosis. The Ki-67 proliferation index was notably higher in aggressive subtypes like DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma, indicating its prognostic relevance. These patterns emphasize the importance of IHC profiling in accurately classifying lymphomas and supporting targeted clinical management.

References

- Rajalakshmi, Priya SS. Spectrum of histopathological diagnosis of lymph node biopsies and utility of immunohistochemistry in diagnosis of lymphoma: A 5 year retrospective study from a tertiary care Centre in South India. Ind J Pathol Oncol 6 (2019): 434–9.

- O'Dowd G, Bell S, Wright S. Wheater's Pathology: A Text, Atlas and Review of Histopathology E-Book: Wheater's Pathology: A Text, Atlas and Review of Histopathology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences (2019) Feb 26.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. World Health Organization classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. WHO Classification of Tumours, Revised 4th Edition. Lyon: IARC (2017).

- Nair R, Arora N, Mallath MK. Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in India. Oncology 91 (2016): 18-25.

- Abdel-Ghafar AA, El MA, Mahmoud HM, et al. Immunophenotyping of chronic B-cell neoplasms: flow cytometry versus immunohistochemistry. Hematology reports 4 (2012): e3.

- Sengar M, Akhade A, Nair R, et al. A retrospective audit of clinicopathological attributes and treatment outcomes of adolescent and young adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas from a tertiary care center. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology 32 (2011): 197-203.

- Dewan K, Mann N, Chatterjee T. Comparing flow cytometry immunophenotypic and immunohistochemical analyses in diagnosis and prognosis of chronic lymphoproliferative disorders: Experience from a Tertiary Care Center. Clinical Cancer Investigation Journal 4 (2015): 707-12.

- Ferry JA. Extranodal lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 132 (2008): 565-78.

- Dardenn AJ, Stanfeld AG, Ardenne D. Lymph node biopsy interpretation 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone (1992).

- Dave DV, Patel DB, Popat DVC. Comparison of immunohistochemistry with conventional histopathology for evaluation of lymphnodes. Int J Clin Diagn Pathol 5 (2022): 80–4.

- Connors JM. Clinical manifestations and natural history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Cancer Journal 15 (2009): 124-8.

- Naresh KN, Srinivas V, Soman CS. Distribution of various subtypes of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in India: a study of 2773 lymphomas using REAL and WHO Classifications. Annals of oncology 11 (2000): S63-7.

- Borgohain M, Krishnatreya K, et al. Diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry in lymphoma. International Journal of Contemporary Medical Research 4 (2017): 6-9.

- Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood 107 (2006): 265-76.

- Aggarwal D, Gupta R, Singh S, et al. Comparison of working formulation and REAL classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis of 52 cases. Hematology 16 (2011): 195-9.

- Dey BP, Chakravarty S, Kamal M. Flow cytometry of lymph node aspirate can effectively differentiate the reactive lymphadenitis from the nodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University Journal 10 (2017): 219-26.

- Alam SM, Khaled A. Immunophenotypic characteristics of Diffuse Large Bcell Lymphoma. Bioresearch Communications 8 (2022): 1049-52.

- Jahan JA, Islam SR, Tanim MS, et al. Analysis of the association between Epstein Barr virus infection and Hodgkin lymphoma. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University Journal 15 (2022): 32-6.

- Sapkota S, Shaikh H. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. StatPearls 27 (2020).

- Aslam W, Habib M, Aziz S. Clinicopathological Spectrum of Hodgkin's and Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: A Tertiary Care Cancer Hospital Study in Pakistan. Cureus 14 (2022): e25620.

- Akhter A, Rahman MR, Majid N, et al. Histological subtypes of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma in different age and sex groups. Bangladesh Medical Journal 41 (2012): 32-6.

- Lisa M, Verma PK, Mustaqueem SF. Distribution of Lymphoma Subtypes in Bihar—Analysis of 518 Cases Using the WHO Classification of Lymphoid Tumors (2017). Journal of Laboratory Physicians 12 (2020): 103-10.

- Adomako J, Abrahams AOD, Dei-Adomakoh YA. Immunophenotypic characterisation of non-Hodgkin lymphomas at a tertiary hospital in Ghana. Ecancermedicalscience 16 (2022): 1458.

- Skinnider BF, Horsman DE, Dupuis B, et al. Bcl-6 and Bcl-2 protein expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma: correlation with 3q27 and 18q21 chromosomal abnormalities. Hum Pathol 30 (1999): 803-8.

Impact Factor: * 6.2

Impact Factor: * 6.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.33%

Acceptance Rate: 76.33%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks