Informal Caregivers’ Role in Preventing Falls in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: A Scoping Review

Carolyn Tran1, Dr. Munira Sultana2*

1Department of Psychology, University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada

2Biomedical Sciences, University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Dr. Munira Sultana, Biomedical Sciences, University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada

Received: 21 November 2025; Accepted: 28 November 2025; Published: 09 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: Carolyn Tran, Munira Sultana. Informal Caregivers’ Role in Preventing Falls in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: A Scoping Review. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 9 (2026): 17-24.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Informal caregivers play a crucial role in preventing falls in Canadian older adults with cognitive impairment, yet little is known about the supports available to them. This scoping review aimed to map the existing supports and programs available to informal caregivers of older adults with cognitive impairment for fall prevention and to identify gaps in current resources. We searched seven academic databases and various grey literature sources. Eligible studies focused on Canada, involved informal caregivers of older adults with cognitive impairment, and addressed falls or fall-prevention supports. Findings were synthesized using content analysis. Out of 1,487 records, we identified five peer-reviewed studies and 15 grey literature sources that met our eligibility criteria. The results indicated that informal caregivers frequently expressed concerns about fall risk, yet few studies reported actual engagement with formal fall-prevention resources. While the grey literature highlighted some fall-prevention resources, these supports were often fragmented and hard to locate. This review found that the role of informal caregivers in fall prevention is both under-recognized and under-supported in Canada. Future work should explore caregivers’ help-seeking behaviours, their awareness of available supports, and the barriers they face in implementing fall-prevention measures.

Keywords

Informal caregiving; Fall prevention; Cognitive Impairment; Aging

Informal caregiving articles; Fall prevention articles; Cognitive Impairment articles; Aging articles.

Article Details

Introduction

Among individuals aged 65 and older, falls are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalizations and serious injuries in Canada [1]. The risk of falling increases even more if the patient has cognitive impairment, with 16% of hospital admissions by seniors with dementia being fall-related compared with 7% among other seniors [2]. In 2018, the financial impact of falls-related injuries among older adults in Canada was estimated at around $5.6 billion, which is twice the expense associated with those aged 25 to 64 [1]. A recent report has highlighted the consequences of falls for older individuals, noting that over 34.4% of these incidents led to hip fractures. This complication extended the average hospitalization duration, increasing it from 4 to 5 days to 7 to 8 days [1]. Falls and the injuries they cause not only diminish one’s quality of life but also result in higher caregiver demands and can lead to more admissions to long-term care facilities. Research indicates that fall prevention initiatives for cognitively healthy older adults may be less effective for those with cognitive impairment [3]. However, a recent study has found that the involvement of informal caregivers, typically family members, friends, or other unpaid supports, may play a crucial role in fall prevention among older adults with cognitive impairment [4]. These caregivers often manage a range of responsibilities, including personal care and household tasks, as well as ensuring the safety of the home environment. The pressures associated with informal caregiving can impact one’s well-being, with statistics indicating that one-third of caregivers experience distress, which may manifest as feelings of anger, depression, or being overwhelmed by caregiving responsibilities [5]. On average, informal caregivers of seniors with dementia provide 26 hours of care each week compared to caregivers of those without dementia, who provide 17 hours of care [6]. Additionally, informal caregivers may face financial burdens, as they often incur out-of-pocket expenses for home modifications, professional healthcare services, hiring extra assistance, and other costs. These expenses result in an annual expenditure of about $5,800 [6,7].

A central concern for informal caregivers is fall prevention, as the fear of falls can significantly impact both the caregiver’s daily routines and their decisions regarding long-term care options [8]. However, caregivers may not always be aware of, have access to, or receive adequate support in using fall-prevention resources [9]. Despite the critical role of informal caregivers in maintaining safety for their care recipients with cognitive impairment, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of synthesis on the supports available to them in the Canadian context, particularly in Ontario, where provincial policies and community programs vary. While research has documented caregiver burden and stress, less attention has been paid to the specific issue of falls and how caregivers are supported in preventing them. Recognizing this gap, a scoping review was selected as the most suitable approach. Unlike systematic reviews, which assess the effectiveness of interventions, scoping reviews are well-suited for exploratory objectives, such as mapping the breadth of evidence, identifying existing supports and programs, and highlighting gaps where further study or policy development is needed [10].

Present Study and Research Questions

Using the scoping review framework proposed by [11], this scoping review aims to map existing supports and programs available for informal caregivers of older adults with cognitive impairment, with a focus on fall prevention. Moreover, this scoping review aims to identify gaps in support that informal caregivers may be facing. Such gaps may be related to a specific population, types of support, delivery methods, or whether existing interventions are effective. The following research questions guided the current scoping review:

- In Canada, what supports are available to informal caregivers to prevent falls in older adults with cognitive impairments?

- What are the existing gaps, if any, in current supports?

- What opportunities are there for improving/sustaining current supports?

Systematic Review Protocol and Search Strategy

In this scoping review, we examined several databases, including CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Scopus, AgeLine, Social Services Abstracts, and Sociological Abstracts. These databases were selected to ensure that the topic of caregiver experiences with older adults who have cognitive impairments is explored from various perspectives. For instance, CINAHL and AgeLine focus on nursing and allied health articles related to fall prevention [9]. In contrast, PsycINFO may provide studies on the psychological aspects of being an informal caregiver (e.g., [12]). Additionally, incorporating sociological databases could help capture information about social policies and available caregiver resources in community settings. We also reviewed grey literature in this field to understand the initiatives and services provided by Canadian, specifically Ontario, public health services and organizations for this population, as grey literature tends to be excluded from similar scoping reviews [13]. The grey literature included resources from dissertations, Canadian or Ontario government websites, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), among others.

A combination of broad terms was used within each database (Table 1). I opted to use broad search terms because the preliminary results of specific terms (e.g., caregiv* vs informal caregiver) yielded little to no results. Therefore, these broad search terms aimed to generate as many results as possible. Some databases were unable to produce results when using the key term “Canada,” so the identification of the Canadian context was screened during full-text review.

It is important to acknowledge that this review focuses exclusively on the Canadian healthcare system, specifically with a focus on Ontario. Studies conducted outside of Canada, such as those in the United States, were excluded from this scoping review. To ensure methodological integrity and to avoid selection bias, the co-authors adopted the search strategy and eligibility criteria through a series of iterative discussions.

Table 1. Databases, Search Terms, and Results

|

Disciplines |

Database |

Keywords / Search strings |

Total Results |

|

Nursing and Allied Health |

CINAHL |

caregiv* AND (elderly or aged or older or elder or geriatric or elderly people or old people or old people or senior) AND (dementia or cognitive impairment) AND fall* AND (intervention or program) |

112 |

|

AgeLine |

caregiv* AND (elderly or aged or older or elder or geriatric or elderly people or old people or old people or senior) AND (dementia or cognitive impairment) AND fall* AND (intervention or program) |

4 |

|

|

MEDLINE |

caregiv* AND (older adults OR elderly) AND (cognitive impairment OR dementia) AND fall* AND (support OR intervention) |

167 |

|

|

Psychology |

PsycINFO |

caregiv* AND (older adults OR elderly) AND (cognitive impairment OR dementia) AND fall* AND (support OR intervention) |

55 |

|

Sociology |

Social Services Abstracts |

caregiv* AND (elderly or aged or older or elder or geriatric or elderly people or old people or old people or senior) AND (dementia or cognitive impairment) AND fall* AND (intervention or program) |

187 |

|

Sociological Abstracts |

caregiv* AND (elderly or aged or older or elder or geriatric or elderly people or old people or old people or senior) AND (dementia or cognitive impairment) AND fall* AND (intervention or program) |

222 |

|

|

Multidisciplinary |

Google Scholar [first 50 pages] |

("informal caregiver*" OR "family caregiver*" OR "unpaid caregiver*") |

508 |

|

Scopus |

caregiv* AND (elderly or aged or older or elder or geriatric or elderly people or old people or old people or senior) AND (dementia or cognitive impairment) AND fall* AND (intervention or program) |

86 |

|

|

Grey Literature |

Google.ca |

older adults dementia support services Canada programs caregiver” fall OR “family “informal caregiver” filtered by location: Canada |

146 |

|

Total number of articles |

1487 |

Eligibility Criteria

To be considered for full-text review, a study had to satisfy the following criteria: 1) Studies, programs, or reports conducted in Canada or specific to the Canadian context, 2) Peer-reviewed studies (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods), 3) Population: informal caregivers caring for older adults (typically aged 60+), 4) Care recipients must have cognitive impairments (e.g., dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment), 5) Mention of falls, fall prevention supports, programs, strategies, or services (e.g., education, training, environmental modifications, mobility aids, caregiver support, or risk assessment), 6) Written in English. As for grey literature, the resources must be Canadian or Ontario government or NGO reports, toolkits, policy briefs, dissertations, and evaluations of programs within the last five years. Records identified must be in English to reduce the possibility of misinterpretation or errors that may arise from translation, since both authors are fluent in English. The policy documents must be dated within the last five years, as policies have evolved since the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies were excluded if they failed to meet any of the following criteria: 1) Studies outside of Canada, 2) Editorials, opinion pieces, news articles (unless they contain original data or program description), 3) Reviews or scoping reviews, 4) Formal or professional caregivers (e.g., nurses, PSWs) unless they are co-supporting informal caregivers, 5) Care recipients without cognitive impairment or not clearly described as having it, 6) no mentions of falls, 7) Supports only focused on care recipients (older adults) without caregiver engagement, 8) Studies focused exclusively on institutional settings (e.g., long-term care homes), unless they include transitional or home-based caregiver supports, 9) Settings that are highly clinical without caregiver involvement (e.g., hospital-only falls assessments), and 10) Non-English.

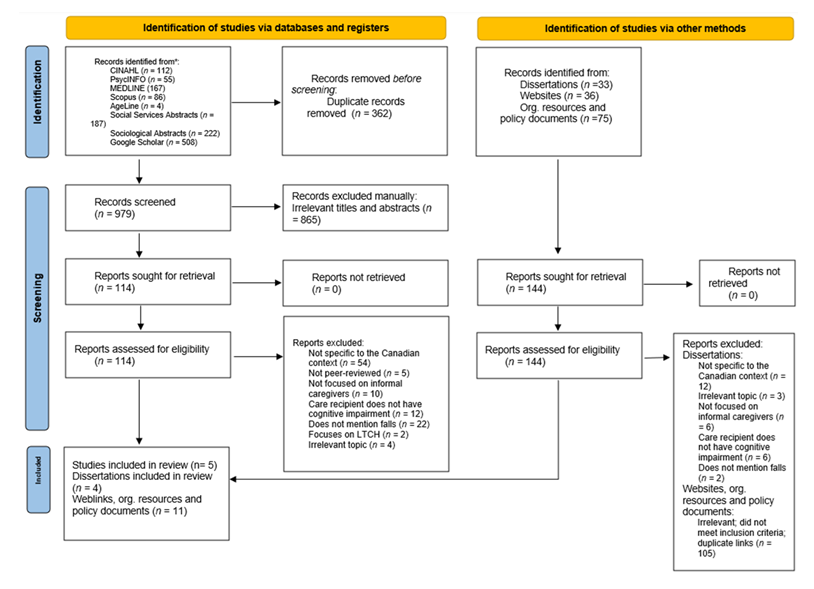

Data Extraction

Database searches identified a total of 1,487 records. After removing duplicates, 979 articles were screened for full-text review. Articles were removed if they were irrelevant or if the titles and abstracts did not meet the eligibility criteria (n = 865). Articles with ambiguous abstracts, such as those including older adults with and without cognitive impairment, or those that did not state the location of their study, were included in the reports sought for retrieval and assessed for eligibility (n = 114). While reviewing full-text articles, screening was heavily focused on the Canadian context, specifically whether the article was peer-reviewed, whether it mentioned informal caregiver experiences (e.g., caregiver burden), and whether the care recipient was identified as being cognitively impaired. The final eligibility criteria include mentions of fall or fall prevention supports, programs, strategies, or services. Five studies were included in the review. The lack of studies that focus on caregivers’ experiences with fall prevention and support for their care recipients is considered a knowledge gap in the current literature, which will be discussed later.

For grey literature, 33 dissertations and 111 files and weblinks were assessed for eligibility. Those that were excluded had reasons such as not being specific to the Canadian context, being irrelevant to the current topic, or being policy documents that were older than 5 years (n = 134). Hence, four dissertations, 11 weblinks, and files met the eligibility criteria for full review. The study selection process and the characteristics of the excluded studies are presented in a flow chart (Figure 1), following PRISMA guidelines [14].

Analysis of Evidence

For this scoping review, we chose to conduct a content analysis to analyze the results [15]. Content analysis organizes and summarizes the findings of qualitative research into frequency counts and themes, providing a systematic approach to interpreting the data. It is flexible and can be applied to various types of documents, including interview scripts, websites, and images. Moreover, it is generally used to describe human experiences and perspectives, providing meaningful descriptions, but it does not aim to explain these experiences [16]. This final decision to analyze the results using content analysis was influenced by the number of research articles and dissertations that employed qualitative or mixed methods (n = 9). This scoping review identified five empirical articles: four qualitative studies and one quantitative study. Four qualitative dissertations were identified, as well. Additional grey literature, such as weblinks, was used to identify accessible resources for informal caregivers of older adults with cognitive impairment.

Results

The results of this scoping review partially answered our research questions. This review offered valuable insights into the current state of fall prevention support utilized by informal caregivers who care for older adults with cognitive impairments. By examining a variety of information sources, including research studies and grey literature, we identified 1) the experiences of informal caregivers, 2) the supports available to them, and 3) the potential challenges they face in accessing fall prevention resources for their family members. However, the scoping review did not identify opportunities for improving/sustaining current supports, as there appears to be a gap in using these supports. The following sections present the findings gathered from our scoping review.

Findings from Journal Articles and Dissertation Studies

Findings from journal articles and dissertation studies did not fully answer our research questions. However, they informed our understanding of the informal caregivers’ experiences while caring for a loved one with cognitive impairment. Three main themes were identified from the included studies: caregivers’ concerns about falls, the burdens of caregiving, and the need for additional support. These themes identified the challenges that informal caregivers face that may prevent them from accessing fall prevention support.

Caregivers’ Concerns About Falls

All (n = 9) the identified articles and dissertations focused on the experiences of informal caregivers, and falls were highlighted as one of the concerns that informal caregivers had about their loved ones. Caregivers in these studies discussed the impacts of caring for a family member with dementia, including how caregiving affected their lives and how they coped with these changes [12]. A recurring theme across the studies was the worry about leaving their family member alone, particularly the fear that their loved one might fall without anyone to assist them. This amount of worry resulted in sleep loss [17]. Overall, participants acknowledged the risks associated with leaving their family member alone and falling [18,8].

The Burdens of Caregiving

The review also identified potential solutions to ease caregiver burden. A tool to reduce the risk of falls and to relieve some caregiver burden included encouraging a loved one to use a mobility aid, such as a walker [19]. However, caregivers were still involved in ensuring that their loved ones use their mobility aids properly and consistently. Additionally, the review identified a program (the Namaste Care Program) designed to enhance the quality of life for people with dementia and their caregivers, for use at home [20]. However, the source documents cautioned that utilization of these supports might require allocating time for training with a healthcare professional to ensure adequate implementation. Moreover, such programs did not fully address the need to keep the care recipient accompanied throughout the day, which would ease the caregivers’ concerns about their risk of falls and caregiver burden. Moreover, the findings indicated that informal caregivers may face challenges in implementing these solutions, primarily due to the time commitment and inconvenience of such programs [20]. These studies [19,20] indicated that although there may be support for caregivers, caregivers’ lack of time and constant concerns for their loved ones may pose a barrier to using various support resources.

The Need for Additional Support

Additional studies (n = 5) have emphasized the need for increased home-based care support for informal caregivers [21], as well as the integration of technology [22], mobility aids to help prevent falls [19], or just needing the presence of someone in the home for more extended periods of time instead of daily short visits [23]. In certain situations, such as when it was necessary to work or when it was unsafe for a family member to remain home alone, some participants considered long-term care home options for their loved ones. However, falls still occurred in these settings due to insufficient staff monitoring of residents on a one-to-one basis [8].

Findings from Weblinks

Support from Health Organizations

The grey literature identified different forms of resources, including resources for general informal caregiving [24], dementia care [25], local resources [26], and government sites [27,28]. Some caregiving-related websites recommended that informal caregivers receive support, training, and education to handle tasks related to informal caregiving [5,29]. The support should include training and continuing education to enable caregivers to stay up-to-date with new equipment, technologies, and therapies for their loved ones [30]. There was an overlap in some of the websites, as they appeared to form a network, with numerous websites referring users to related sites. For example, the majority (n = 6) of webpages refer to the Alzheimer’s Society of Canada as a resource. A deeper dive into these websites found that fall prevention was not on the homepages. To find this resource, users must specify it in the search bar. Using keywords like “falls” or “fall prevention” within these websites will redirect caregivers to resources, such as day programs to help with fall prevention [31], or handouts on how to make home modifications to reduce one’s likelihood of falling [32,33]. Again, caregivers would have to utilize the search bar to locate this resource.

Support from the Canadian Government

When reviewing the Canadian federal webpage for supports related to aging in place and caregiving, it was noted that the federal government had legislation in place that requires provinces and territories to provide coverage for health services under the Canada Health Act. In addition, the federal government also provided some financial support. One of them was the Canada Caregiver Credit, a non-refundable tax credit that could be claimed by individuals who regularly support immediate relatives due to a physical or mental impairment. Additionally, the federal government might support initiatives to increase the availability of and delivery of community services across Canada. While the Canadian federal government played a role in providing funding for health services, each province and territorial government was responsible for administering their healthcare systems, which meant that support for informal caregiving would vary across the country [27].

In this scoping review, we focused on Ontario’s support for informal caregivers. These supports included home and community support services, such as assessments for home care options, care in the community, and respite services that aimed to give caregivers a break or rest [28]. Several tax credits were available, including disability tax credits, medical expense tax credits, and caregiver credits. Additionally, seniors aged 70 or older may be eligible for the Ontario Seniors Care at Home Tax Credit to cover certain medical expenses [28]. Ontario also offered benefits for caregivers so they do not have to choose between their jobs and caring for their family. These benefits included compassionate care benefits (providing up to 26 weeks of employment insurance benefits for temporary absences from work to provide end-of-life care), Ontario’s family medical leave, and family caregiver leave, which ensures that an employee retains their job while caregiving for a family member [28]. While these benefits existed, the latter-mentioned are unpaid leaves, with the benefit of job security [28].

Identified Gaps

Findings from this scoping review identified a gap in the use of caregiver supports for fall prevention among older adults with cognitive impairment. Although caregivers frequently expressed concern about the risk of falls, there was little evidence that they accessed or used formal fall-prevention resources [12,18]. While the included studies did not centre on falls as a primary focus, falls were described as one of several ongoing worries that shaped caregivers’ daily lives.

Discussion

A notable disconnect emerged between the peer-reviewed and grey literature. While empirical studies have documented caregivers’ concerns and burdens, they rarely report actual engagement with fall-prevention supports, except for encouraging their loved ones to use a mobility aid [19]. By contrast, grey literature searches revealed that resources are available through Alzheimer Society chapters, Ontario Health atHome, CIHI, and local healthline.ca portals. However, these resources were not always visible, well-advertised, or tailored to the needs of caregivers. For example, fall-prevention information was rarely located on homepages and required targeted keyword searches (e.g., “fall prevention”) to be found. This finding suggested that availability alone might be insufficient; barriers such as accessibility, awareness, digital literacy, and cultural relevance likely limited caregivers’ ability to use these supports.

The Canadian health system context further complicated matters. While the federal government set broad policies and provided limited caregiver tax credits, provinces and territories administered health and community services. This complexity resulted in fragmented and uneven access to caregiver supports across the country. Caregivers might need to navigate multiple disconnected portals such as government sites, NGO resources, and local health authorities, which increased their cognitive and emotional burden. Technology and innovation presented both opportunities and challenges. Some studies and grey literature pointed to the potential of mobility aids [19], online caregiver education modules [34,25], and home-based programs as strategies to reduce fall risk [33]. While promising, these solutions might still present barriers for caregivers, including time commitment, cost, or the need for additional training [20]. Technology-based interventions could play a significant role in future caregiver support strategies, provided they were designed with caregiver input and supported by adequate training and resources.

Another important observation was the lack of attention to equity and diversity in the identified evidence. Caregivers were not a homogeneous group; yet, few studies had explored how caregiver experiences with fall prevention might differ across cultural, racial, socioeconomic, or rural-urban contexts. This gap was significant given Canada’s diversity and suggested that current resources might not adequately met the needs of all caregiver populations. Overall, the findings of this review highlighted that while informal caregivers played a central role in maintaining the safety of older adults with cognitive impairment, their role in fall prevention remains under-recognized and under-supported. Addressing this gap would require more than just making resources available; it demands deliberate strategies to integrate caregiver supports into fall-prevention planning, improved system navigation, and ensuring that resources are accessible, inclusive, and responsive to the realities of informal caregivers

Conclusions

This scoping review highlighted a critical gap in the Canadian literature. Although informal caregivers consistently reported concerns about falls among older adults with cognitive impairment, few studies or programs directly addressed their role in fall prevention. Existing supports were fragmented, often buried within broader dementia or caregiver resources, and not always accessible or tailored to caregivers’ needs. The findings suggested several implications for policy and practice. For example, caregiver supports needed to be more visible, centralized, and integrated into fall-prevention strategies. More precise guidance, accessible training, and recognition of the time and emotional burden associated with fall prevention need to be included. Ontario-specific programs, such as respite care and caregiver tax credits, offered some relief but might not directly reduce the daily worry about fall risks. While caregivers are central to maintaining the safety of older adults with cognitive impairment, the Canadian evidence base did not yet adequately support them in fall prevention. Overall, there is a need for intervention studies that examine how informal caregivers seek, use, and benefit from fall-prevention resources. Future work should explore caregivers’ help-seeking behaviours, awareness of available supports, and barriers to implementation. In particular, understanding how culturally diverse caregivers’ access to and experience of fall-prevention programs is an important next step. Addressing this identified gap through our scoping review, further evaluation of policy, programming, and research was essential to improving caregiver well-being and reducing fall-related risks for older adults with cognitive impairment

CONFLICTS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2024, February 20). Surveillance report on falls among older adults in Canada. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/surveillance-report-falls-older-adults-canada.html

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018 a). Dementia and falls. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada/spotlight-on-dementia-issues/dementia-and-falls.

- Racey, M., Markle-Reid, et al (2021). Fall prevention in community-dwelling adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 21 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02641-9.

- Sultana, M., Alexander, et al. Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults (2023). Involvement of informal caregivers in preventing falls in older adults with cognitive impairment: a rapid review. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD 92 (3), 741-750. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-221142.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2020, August 6). 1 in 3 unpaid caregivers in Canada are distressed. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://www.cihi.ca/en/1-in-3-unpaid-caregivers-in-canada-are-distressed.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018 b). Unpaid caregiver challenges and supports. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada/unpaid-caregiver-challenges-and-supports.

- Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence. (2022, November). Giving Care: An approach to a better caregiving landscape in Canada. Retrieved September 30, 2025, from https://canadiancaregiving.org/giving-care/.

- Flagler-George, J. (2014). Squeezed in: The intersecting paradoxes of care for immigrant informal caregivers (Doctoral dissertation, University of Waterloo).

- Montero-Odasso, M., Van Der Velde, et al. Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults (2022). World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age and ageing, 51(9), afac205. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac205.

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, et al (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291-1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, et al (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory & Practice, 8 (1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Ploeg, J., Northwood, et al. (2019). Caregivers of older adults with dementia and multiple chronic conditions: Exploring their experiences with significant changes. Dementia 19 (8), 2601-2620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301219834423.

- Kim, B., Wister, et al. (2023). Roles and experiences of informal caregivers of older adults in community and healthcare system navigation: a scoping review. BMJ open, 13(12), e077641. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077641.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, et al (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Mikkonen, K., & Kääriäinen, et al (2020). Content Analysis in Systematic Reviews. In H. Kyngäs, K. Mikkonen, & M. Kääriäinen (Eds.), The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research (pp. 105-115). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6_10.

- MacFarlane, S. (2016). Exploring the lived experiences of daughters/daughters-in-law providing primary informal care to their mothers/mothers-in-law with dementia (Doctoral dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University).

- Stroud, K. (2018). "You have to sometimes be like a bulldog": Filial Caregiver Experiences Supporting their Parents during the Transition from Hospital to Home in Ontario (Doctoral dissertation, University of Guelph).

- Hunter, S. W., Meyer, et al (2020). The experiences of people with Alzheimer’s dementia and their caregivers in acquiring and using a mobility aid: a qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation 43 (23), 3331-3338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1741700

- Yous, M., Ploeg, J., et al (2022). Adapting the namaste care program for use with caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with moderate to advanced dementia: a qualitative descriptive study. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 42 (2), 271-283. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0714980822000174.

- Smith-Carrier, T., Pham, et al (2017). ‘It’s not just the word care, it’s the meaning of the word. . .(they) actually care’: caregivers’ perceptions of home-based primary care in Toronto, Ontario. Ageing and Society 38 (10), 2019-2040. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x1700040x.

- Mo, G. Y., Biss, et al (2020). Technology use among family caregivers of people with dementia. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 40 (2), 331-343. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0714980820000094.

- Symonds-Brown, H. (2021). Understanding How Day Programs Work as Care in the Community for People Living with Dementia and their Families (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta).

- Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence (2025). Caregiver resources. https://canadiancaregiving.org/resources/caregiver-resources/#Ontario.

- Alzheimer Society of Canada (2025). Alzheimer Society of Canada. https://alzheimer.ca/.

- Health services for Ontario - thehealthline.ca. (2025). https://thehealthline.ca/.

- Government of Canada. (2024, August 27). Core community supports to age in community. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/seniors-forum-federal-provincial-territorial/core-community-supports.html

- Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility. (2024, November 28). A guide to programs and services for seniors. ontario.ca. https://www.ontario.ca/document/guide-programs-and-services-seniors.

- (2025, January 29). What to do if you are a First-Time Family Caregiver - Blog articles and videos. https://www.comforcare.ca/blog/what-to-do-if-you-are-a-first-time-family-caregiver_ae119/.

- National Institute on Ageing (2020). An Evidence Informed National Seniors Strategy for Canada - Third Edition. Toronto, ON: National Institute on Ageing.

- ca (2025). Health services for Erie St Clair. https://eriestclairhealthline.ca/.

- Ontario Health at Home (2025, August 27). Ontario Health atHome. https://ontariohealthathome.ca/.

- McGill University (2025). Dementia, your companion guide. Dementia Education Program. https://www.mcgill.ca/dementia/resources/dementia-your-companion-guide.

- Canadian Virtual Hospice (2025). Caregiving Demonstrations. virtualhospice.ca. https://www.virtualhospice.ca/en_US/Main+Site+Navigation/Home/Support/Support/The+Video+Gallery. aspx?type=cat&cid=110f65fd-0447-4e6e-b860-7646e02b997b#video_content_index

Impact Factor: * 6.2

Impact Factor: * 6.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.33%

Acceptance Rate: 76.33%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks